I spoke to a friend today about our shared Bible reading for the week. We covered Genesis 1-6, Psalms 1-3, and Matthew 1-3. It was an interesting juxtaposition of passages, particularly Psalms and Matthew. Psalm 2 talks about God's authority, scoffing (v. 4) at the kings of the earth who try to throw off his control (v. 2-3). Psalm 3 is a psalm of David crying out to God for deliverance and protection, lying down to sleep without fear since the Lord sustains him (v. 5-6). And in Matthew 2 in the midst of the luminous story of the Nativity with its angelic protection and guidance to the different characters' decisions lies the tragic story of the Massacre of the Innocents, where King Herod killed all baby boys two years and under in order to kill the promised newborn king of whom the Magi spoke and thus preserve his own power.

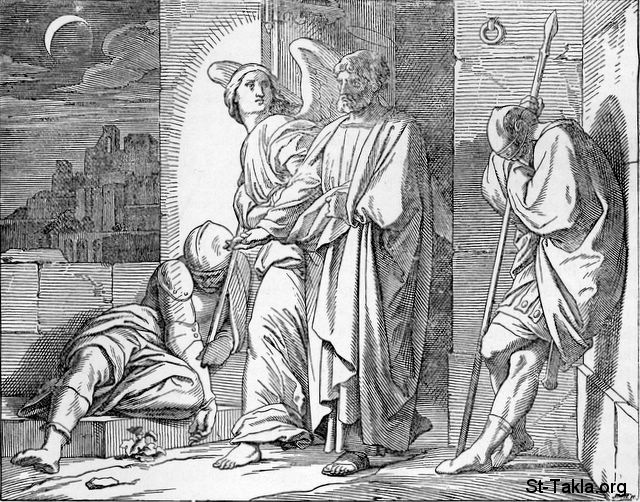

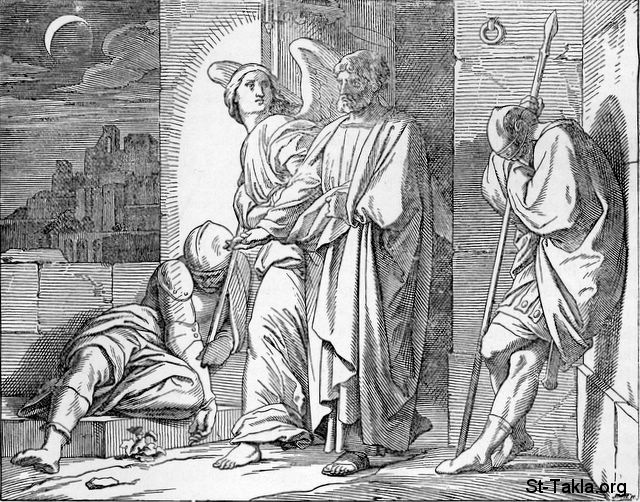

It brought to mind the struggle I often have with trying to grapple with God's ability to do whatever he wants (Psalm 2), his ability to bring peace and protection to his people even in miraculous ways (Psalm 3), and the fact that he does not always do so (Matthew 2). (We faced a similar dilemma in reviewing Acts 12 last night at our small group's Bible study. James the brother of John and later Peter are both imprisoned by Herod Agrippa, the grandson of Herod the Great who murdered the babies and toddlers. James is killed, and Peter is miraculously released by an angel.) How can I trust this God whose decisions on when and how he acts - and doesn't act - so often lie beyond my understanding?

My struggles to trust God end up impacting what I do with fear. I don't like being afraid. So I suppress those emotions and ignore them. I don't want my life to be ruled by fear as many of the things to which God calls me - working with the poor (currently inner-city Philadelphia, future East Africa), living among them, doing cross-cultural work overseas - involve risk, and I want to be obedient to his calling. It helps in my head to know that God could redeem even something awful happening to me, that I would be in far better place in heaven with him if I were to die, that Jesus would walk with me in my pain if my child or husband were to die. But it doesn't change my heart's cry of what to do with all those murdered baby boys in Bethlehem or my cousin murdered in DRC nearly two months ago working for peace or the young man shot outside my house a few weeks ago on a sidewalk where I walk regularly with my toddler and infant. It doesn't change the nightmares of my children being killed or the way my heart races now when I hear loud noises.

A year ago I was wrestling with the same question of trust and the story of Jacob came to mind. On his way back to see his brother Esau, Jacob stops to spend the night beside a stream alone and a man comes and wrestles with him through the night. At the end of the night, he recognizes that he was wrestling God and refuses to let him go without a blessing. In the end, God blesses him and gives him a new name Israel but also touches his hip, giving him a limp. He called the place Peniel, which means "face of God" (Gen. 32:22-32). I prayed at that time that I would continue in my struggle with faith even if it meant struggling in the darkness, alone, or if I left changed or limping. I was sharing with my friend how similar my current struggle feels and felt discouraged that I haven't learned more about how to have faith and trust God in the past year. "But you are doing what you promised," she pointed out. "You're still struggling with God, like Jacob." My eyes mist over at the thought that this lack of perceived progress may not represent failure but instead a type of success.

Ultimately, I think my question of trust is less about what God chooses to do or not to do. It is about whether I believe God is good, no matter whether I understand his choices. If he is good, I can trust him in the inscrutability.

A year ago, as I struggled with fear about my children in the early months of my second pregnancy, I pictured myself walking with Jesus who held out his arms, offering to carry my children. I handed them to him with some reluctance (What if he doesn't give them back? What will I do with empty arms?) but still felt afraid for them and ashamed of my fear. I was invited to picture Jesus' response. As I imagined those warm brown eyes looking at me with love instead of condemnation or even disappointment, the chokehold of fear loosened and dropped away. Jesus, help me to learn to allow myself to sit with my fears before you so that they might lose their strength in my life. Help me to turn to you that I may remember your goodness in the light of your face.

It brought to mind the struggle I often have with trying to grapple with God's ability to do whatever he wants (Psalm 2), his ability to bring peace and protection to his people even in miraculous ways (Psalm 3), and the fact that he does not always do so (Matthew 2). (We faced a similar dilemma in reviewing Acts 12 last night at our small group's Bible study. James the brother of John and later Peter are both imprisoned by Herod Agrippa, the grandson of Herod the Great who murdered the babies and toddlers. James is killed, and Peter is miraculously released by an angel.) How can I trust this God whose decisions on when and how he acts - and doesn't act - so often lie beyond my understanding?

My struggles to trust God end up impacting what I do with fear. I don't like being afraid. So I suppress those emotions and ignore them. I don't want my life to be ruled by fear as many of the things to which God calls me - working with the poor (currently inner-city Philadelphia, future East Africa), living among them, doing cross-cultural work overseas - involve risk, and I want to be obedient to his calling. It helps in my head to know that God could redeem even something awful happening to me, that I would be in far better place in heaven with him if I were to die, that Jesus would walk with me in my pain if my child or husband were to die. But it doesn't change my heart's cry of what to do with all those murdered baby boys in Bethlehem or my cousin murdered in DRC nearly two months ago working for peace or the young man shot outside my house a few weeks ago on a sidewalk where I walk regularly with my toddler and infant. It doesn't change the nightmares of my children being killed or the way my heart races now when I hear loud noises.

A year ago I was wrestling with the same question of trust and the story of Jacob came to mind. On his way back to see his brother Esau, Jacob stops to spend the night beside a stream alone and a man comes and wrestles with him through the night. At the end of the night, he recognizes that he was wrestling God and refuses to let him go without a blessing. In the end, God blesses him and gives him a new name Israel but also touches his hip, giving him a limp. He called the place Peniel, which means "face of God" (Gen. 32:22-32). I prayed at that time that I would continue in my struggle with faith even if it meant struggling in the darkness, alone, or if I left changed or limping. I was sharing with my friend how similar my current struggle feels and felt discouraged that I haven't learned more about how to have faith and trust God in the past year. "But you are doing what you promised," she pointed out. "You're still struggling with God, like Jacob." My eyes mist over at the thought that this lack of perceived progress may not represent failure but instead a type of success.

Ultimately, I think my question of trust is less about what God chooses to do or not to do. It is about whether I believe God is good, no matter whether I understand his choices. If he is good, I can trust him in the inscrutability.

A year ago, as I struggled with fear about my children in the early months of my second pregnancy, I pictured myself walking with Jesus who held out his arms, offering to carry my children. I handed them to him with some reluctance (What if he doesn't give them back? What will I do with empty arms?) but still felt afraid for them and ashamed of my fear. I was invited to picture Jesus' response. As I imagined those warm brown eyes looking at me with love instead of condemnation or even disappointment, the chokehold of fear loosened and dropped away. Jesus, help me to learn to allow myself to sit with my fears before you so that they might lose their strength in my life. Help me to turn to you that I may remember your goodness in the light of your face.